5% of the adult population worldwide experiences depression. If you’re in the United States, your odds of experiencing a major depressive episode nearly double the world average. Individuals and the medical community have grappled with this issue for years, but with limited success.

Could at least part of the answer lie with psychedelics?

The use of psychedelics as a treatment for depression has only recently gained widespread attention from mainstream researchers, but early studies have offered glimpses of exciting potential. In this article, we’ll look at the use of psychedelics as a tool for the treatment of depression. This will include scientific insights, potential benefits, practical tips for microdosing and high dose journeys and safety considerations.

First, a disclaimer: I am neither a doctor nor a lawyer, so nothing in this article should be taken as medical or legal advice. Always consult with a medical professional before embarking on a new course of treatment for any physical or mental issue. Myndfull Health and its affiliates can not and do not promote illegal activity of any kind, so check your local laws before attempting anything in this or any of our other materials.

Depression, its prevalence and the challenge of treatment

Depression is a common mental disorder representing a complex of symptoms including sadness and irritability, accompanied by physical and perceptual changes that impact sufferers’ capacity to function and quality of life.

According to the World Health Organization, about 280 million people worldwide, or about 5% of adults, experience depression (World Health Organization, 2023). Although treatment rates have increased over recent decades, more people are suffering from depression than ever (Ormel et al., 2019).

A 2016 metastudy reported that only about 30% of patients get better with conventional treatment. For context, around 20% of people typically improve without intervention anyway within 3 months. 12% of patients using conventional treatments and medications actually got worse (Kolovos et al., 2017).

In addition to a lack of consistent effectiveness for many people, traditional antidepressant medications are also associated with negative side effects, including weight loss, drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, headaches, suicidal thoughts, sexual dysfunction, and increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular problems (Braund et al., 2021).

Psychedelics as potential tools

The powerful effect psychedelics can have on mood and personal outlook have been well known in the underground community for decades. However, they have been attracting the interest of healthcare professionals and citizen scientists in a more explicitly purposeful context in recent years.

In 2017 the FDA signaled an interest in psychedelic substances as tools for improving mental health by granting breakthrough therapy status to MDMA for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Breakthrough Therapy is an official designation meant to speed up the development and review of drugs to treat serious conditions. This was followed by Breakthrough Therapy designations for psilocybin in treatment resistant depression (TRD) in 2018 and major depressive disorder (MDD) in 2019.

Psilocybin and depression

Psilocybin and its laboratory-synthesized analogs are probably the best studied psychedelic for the treatment of depression. To talk about the role it might play in the treatment of depression, let’s start with how it works in the brain.

How psilocybin affects the brain:

Psilocybin (what most people know as the primary active ingredient in so-called “magic mushrooms”) is metabolized into psilocin after consumption. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll refer to the two interchangeably in this article. Psilocin is special because it happens to activate a certain type of receptors in the brain the way serotonin normally would. This allows it to change the behavior of the associated nerve cells and meaningfully impact the way the brain functions (Kwan et al., 2022).

These receptors, known as 5HT2A receptors, are located throughout the brain. However, they are particularly concentrated in parts of the brain associated with learning and cognition, contextual awareness, and sensory perception–especially vision.

Because of its ability to “mimic” serotonin and activate serotonin receptors, an influx of psilocybin in the brain can cause visual hallucinations and profound changes to mood and perception. Serotonin is usually released in a highly controlled way, so the broad application of psilocybin can temporarily stimulate new connections and de-emphasize old ones. For this reason, psilocybin can open windows of opportunity to break out of set patterns of thought and behavior (Carhart-Harris, 2018).

Aside from its action on 5HT2A receptors, psilocybin (and LSD for that matter) has been shown to stimulate structural neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is the creation, strengthening or changing of connections in the brain. This happens because of psilocybin’s ability to readily bond to another set of receptors (known as TrkB receptors) that help drive these changes in the brain (Moliner et al., 2023).

What evidence do we have?:

There’s still a lot we don’t know, but psychedelics are no longer purely a matter of hearsay and tradition. After years of being a taboo to the mainstream, we are starting to see a blossoming of empirical data, much of it highly supportive of the potential of psychedelic substances as a tool for the betterment of well people as well as as treatments for depression and other disorders.

An important starting point to consider is safety. A recent metastudy summarizing data from 114 other studies on psychedelics and psychedelic assisted therapy looked at the prevalence of adverse physical or psychological events. They found that across the 3500+ study participants, serious adverse events like worsening depression or suicidality were reported in 4% of participants with pre-existing neuropsychiatric disorders but were absent among healthy participants and (Hinkle et al., 2024). They did not comment on how often those adverse events would normally occur in similar individuals without psychedelics.

Clinical results of the use of psilocybin in the treatment of depression have been very positive. A recent randomized clinical trial looked at participants with major depressive disorder. Over 70% of the participants who received psilocybin-assisted therapy showed a clinically significant response and just over half were in remission (Davis et al., 2020). The researchers concluded that psilocybin given in conjunction with psychotherapy quickly produced significant and sustained antidepressant effects.

The above shows impressive behavioral results, but what about measurable physical evidence? Depression is associated with a withering of neural connections in the neocortex, the serotonin receptor-rich region of the brain where psilocybin exerts much of its influence. Researchers documented measurable increases in density of neural branches in mice. This structural re-wiring was also notable in that it lasted for at least a month (Shao et al., 2021) .

The take-away is that there is some really strong evidence that psilocybin could be a great alternative and/or complement to traditional treatments for depression. Like most courses of treatment, it’s not 100% risk free, especially at high doses, but it does appear to be a reasonably safe option for many people.

Other substances

Ketamine is not a classical psychedelic, but it is frequently lumped with psychedelics as an innovative treatment for depression. Ketamine has been shown to have extremely rapid antidepressant effects, but those effects tend to be more transient than the other main psychedelics (Hibicke et al., 2020). The advantage of ketamine is that it’s a controlled substance in the United States but not illegal. Significantly, esketamine, a close analog of ketamine, is approved by the FDA for treatment resistant depression.

LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) is another classical psychedelic that shares some of its mechanisms with psilocybin. Similar to psilocybin, it can encourage novel connections in the brain and help promote neuroplasticity (Moliner et al., 2023). Also like psilocybin, clinical research suggests that the changes it promotes are likely more durable than ketamine (Hibicke et al., 2020).

The world of psychedelics is, of course, bigger than just psilocybin, LSD and ketamine, but the formal research gets more sparse the more niche the substance you’re looking at. For every psychedelic out there, there’s somebody that says it has helped them with depression.

So which is best? Unfortunately, there’s no one right answer. Psilocybin and LSD are the most common classical psychedelics used, which is great when looking for information or seeking advice from others who have been in your position. Additionally, the short term effects of ketamine are impressive if approached with realistic expectations. In the end, it will often depend on the subject’s needs and personal biology and psychology.

Microdosing for depression

Although most of the research on treating depression with psychedelics focuses on infrequent, high-dose experiences (sometimes called macrodoses), psychedelic microdosing has grown steadily in popularity in the last decade.

Psychedelic microdosing is the regular consumption of small amounts of a psychedelic substance or substances–usually about 1/10 of a standard dose. It is done with the intention to enhance or treat one’s self in some way. In theory, the substance is still able to do its work acutely and cumulatively over time, but because a microdose is so small, the user’s experience will normally be below the hallucinogenic threshold. They should therefore be able to carry on with their daily activities unimpaired.

According to survey data, nearly a third of people that microdose psychedelics do so for mood enhancement. On top of that, about another 1 in 7 do so specifically as a therapeutic treatment–normally for some psychological concern (Hutten et al., 2019).

The evidence for microdosing and depression

A quick review of the various online forums about microdosing reveals volumes of individual anecdotal experiences of the reported benefits and limitations of microdosing for depression. According to many first hand accounts, even microdosing for a while and then stopping seems to cause a long-term improvement in depression for some people.

The evidence is not limited to self-reporting. A 2019 study recorded the experiences of 98 microdosers of various psychedelic substances and measured their mood, focus, sense of agency and other attributes. They observed a general improvement in reported psychological function on all measures on dosing days, and before and after measures showed reductions in reported levels of depression and stress (Polito & Stevenson, 2019).

Another study followed nearly 1,000 psilocybin microdosers for just 30 days and found small to medium-sized improvements in mood and mental health across diverse subjects (Rootman et al., 2022).

So is it better to go high-dose or microdose for depression?

There are a few factors to consider when determining what the best course is for you.

First, what’s your risk tolerance? Macrodosing has great upside potential, but it also has a higher chance of a negative experience. This doesn’t usually mean physical danger, but it can be quite unpleasant. Microdosing is more gradual but you’re much less likely to have a dramatically negative experience.

Related to the above, what does your support system look like? Full-strength psychedelic therapies are often administered in conjunction with traditional talk therapy to aid in integration. Do you have someone to fill that role? If you’re on your own or just corresponding with people on an online forum, you might want to start off with microdosing.

Another consideration is your access to the medicine. Do you have a consistent source that will allow you to dial in a microdosing regimen and stick to it? If so, that’s could be a great, sustainable option. If you only have a set amount because it’s been gifted to you or something like that, it might be difficult to cultivate a long-term practice.

Ultimately, the choice is yours. Similar to traditional depression treatments, what works well for one person might not work for another. You just need to try it, practice patience with yourself, and listen to your body and your intuition. There’s also no rule against mixing and matching. Lots of people do big journeys once or twice a year to reset and then microdose as needed in between.

Steps to take before using psychedelics for depression

Depression is a serious condition, and any course of treatment should be approached thoughtfully. In addition to this basic fact, bringing psychedelics into your treatment plan calls for some additional considerations.

Legality is one particular factor to consider. Although psychedelics are gaining awareness in the mainstream and have helped many people, most of them are still illegal in most of the United States and the world. Their sale and possession can attract serious penalties, so it is highly advisable to check your local laws.

It’s also a good idea to consult a healthcare or mental health professional to get a second opinion. There are several conditions and medications that might disqualify psychedelics outright. You also might just not be in the right place emotionally right now.

If you’re already on an antidepressant, an important consideration is what your approach will be to that. SSRIs and SNRIs have a reputation for dampening the effects of classical psychedelics (Gukasyan et al., 2023). The safest choice is to continue with your current treatment until you’re sure you’re ready. Not everyone experiences the suppressing effects, and even if you do, it’s better to adjust your dosage to accommodate than quit cold turkey and risk making things worse.

Macrodosing for Depression: Practical Tips

Minimize background distractions: If you have particular upheaval in your life, or you’re just in a bad place, consider if now is the best time for major inner work. Psychedelics are often referred to as non-specific amplifiers. If you go into a high-dose session from a place of high anxiety, that may impact your experience and make it more difficult.

Be intentional: A high-dose psychedelic experience for the purpose of treating depression is not the same as tripping for fun. It should be approached thoughtfully, with a concrete idea of what you’re trying to achieve. It should also be given your full attention to make the most of it.

Find a support person: Support is an important part of the healing process. Much of the successful clinical research pairs psychedelics with talk therapy. At the very least you should have someone to talk to about your experience, and if you’re not experienced with psychedelics, having a trip sitter or guide you trust to look out for you can be very helpful.

Minimize visual stimulus: Because psychedelics are so closely associated with optical perception, it’s easy for visual stimulus to dominate your experience. Many clinical protocols actually call for blindfolding as a means of focusing the patient on their thoughts and feelings. Don’t let the visuals distract you from your intention.

Consider a 2-dose approach: Some psychedelic therapists recommend using 2 separate sessions separated by about a week when working with high doses. The first is a lower “safety” dose to familiarize the participant with the experience and validate tolerability. The second is a higher strength dose to do the heavy lifting without having to worry as much about adverse events (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016).

Take time to reflect: Taking time to reflect on your experience after the fact and consider what the psychedelic experience has shown you can help you integrate the lessons for long-term change.

Microdosing for Depression: Practical Tips

Pick a protocol: A protocol is a set schedule of days when you do and do not take your microdose. There are lots of protocols, including the Fadiman Protocol and the Stamets Protocol, and there’s no one right way.

With that said, a common sentiment among many people microdosing for mental health is a preference for consistency. These people often choose to pursue a 1 day on, 1 day off repeating schedule to ensure steady support while avoiding building tolerance.

Start low, go slow: Finding the right dose for your sweet spot is an important first step. Ideally, you want to start with the smallest dose that could be beneficial and work your way up to find your own optimal dose. If you find that you’ve exceeded your level of comfort, you can just dial it back down–hopefully with limited impact.

Set an intention: Just like with higher doses, microdosing isn’t necessarily as simple as just popping a pill and going about your day to let the medicine do the work. You will likely see better results by considering what you hope to achieve.

Track your experience: On a similar note to setting an intention, tracking your microdoses can be helpful in monitoring your progress and tailoring your approach. By tracking your doses, how you felt each day, what else was going on and so forth, you will identify patterns of what works best for you in what situations so you can get the most out of your practice.

Combine microdosing with lifestyle changes: Microdosing may help you with your depression, but it won’t do all the work for you. Making positive changes to your lifestyle like exercising, getting enough sleep or adopting some form of mindfulness practice will likely help you along your way.

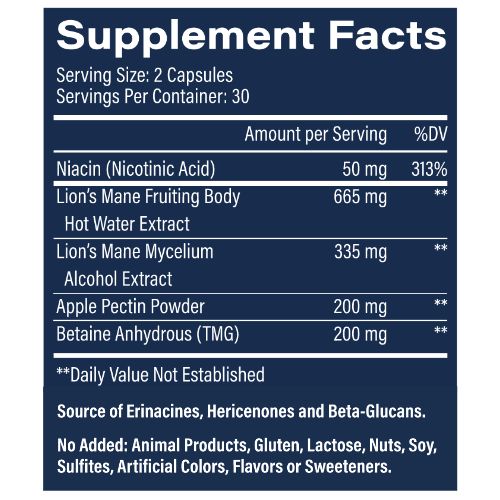

Stacking: Many people combine their microdoses (and macrodoses, for that matter) with a specialized supplementation regimen. There are many variations, but the most popular is the combination of psilocybin with lion’s mane mushroom and niacin to boost the neuroplastic effects of psychedelics (Stamets, 2023). In fact, there are now specialized microdosing support supplements available that are formulated explicitly to enhance microdosing results.

Be patient with yourself: If they do their homework and approach microdosing thoughtfully and with discipline, most people report benefits. Give yourself the time and grace to make progress gradually.

Conclusion

Depression is a serious condition that impacts the lives and livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people worldwide. We are diagnosing and treating people at a higher rate than ever before, but our mainstream treatments still fail a lot of people.

Psychedelics offer an intriguing new approach that may hold the potential to help a lot of people.

However, it is important to recognize that psychedelics are a tool, not a cure. They can help break a person out of a rut and create the conditions for lasting change, but the person using them needs to play an active role. They initiate the process, but they are not the process itself.

Remember: you don’t have to do it alone. A strong support network, potentially including professional help can help immensely–especially if your depression is severe. A good counselor/therapist/psychologist may help you get to the root of the causes of your issues to properly address them long term.

Everyone is different, and psychedelics may or may not be the solution for you. Mental health is complicated, and mainstream psychiatrists often use trial and error to find the correct dose and meds for patients. If you want to try something different, psychedelics could be just what you’re looking for.

Sources

Braund, T. A., Tillman, G., Palmer, D. M., Gordon, E., Rush, A. J., & Harris, A. W. F. (2021). Antidepressant side effects and their impact on treatment outcome in people with major depressive disorder: an iSPOT-D report. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01533-1

Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2018). The entropic brain - revisited. Neuropharmacology, 142, 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.03.010

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M. J., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., Bloomfield, M., Rickard, J. A., Forbes, B., Feilding, A., Taylor, D., Pilling, S., Curran, V. H., & Nutt, D. J. (2016). Psilocybin with Psychological Support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label Feasibility Study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(16)30065-7

Gukasyan, N., Griffiths, R. R., Yaden, D. B., Antoine, D. G., & Nayak, S. M. (2023). Attenuation of psilocybin mushroom effects during and after SSRI/SNRI antidepressant use. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 026988112311799-026988112311799. https://doi.org/10.1177/02698811231179910

Hibicke, M., Landry, A. N., Kramer, H. M., Talman, Z. K., & Nichols, C. D. (2020). Psychedelics, but Not Ketamine, Produce Persistent Antidepressant-like Effects in a Rodent Experimental System for the Study of Depression. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 11(6), 864–871. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00493

Hinkle, J. T., Graziosi, M., Nayak, S. M., & Yaden, D. B. (2024). Adverse Events in Studies of Classic Psychedelics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2024.2546

Hutten, N. R. P. W., Mason, N. L., Dolder, P. C., & Kuypers, K. P. C. (2019). Motives and Side-Effects of Microdosing With Psychedelics Among Users. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 22(7), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyz029

Kolovos, S., van Tulder, M. W., Cuijpers, P., Prigent, A., Chevreul, K., Riper, H., & Bosmans, J. E. (2017). The effect of treatment as usual on major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 72–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.013

Kwan, A. C., Olson, D. E., Preller, K. H., & Roth, B. L. (2022). The neural basis of psychedelic action. Nature Neuroscience, 25(11), 1407–1419. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-022-01177-4

Moliner, R., Girych, M., Brunello, C. A., Kovaleva, V., Biojone, C., Enkavi, G., Antenucci, L., Kot, E. F., Goncharuk, S. A., Kaurinkoski, K., Kuutti, M., Fred, S. M., Elsilä, L. V., Sakson, S., Cannarozzo, C., Diniz, C. R. A. F., Seiffert, N., Rubiolo, A., Haapaniemi, H., & Meshi, E. (2023). Psychedelics promote plasticity by directly binding to BDNF receptor TrkB. Nature Neuroscience, 26(6), 1032–1041. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-023-01316-5

Ormel, J., Kessler, R. C., & Schoevers, R. (2019). Depression: more treatment but no drop in prevalence: how effective is treatment? And can we do better?. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 32(4), 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0000000000000505

Polito, V., & Stevenson, R. J. (2019). A systematic study of microdosing psychedelics. PLOS ONE, 14(2), e0211023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211023

Rootman, J. M., Kiraga, M., Kryskow, P., Harvey, K., Stamets, P., Santos-Brault, E., Kuypers, K. P. C., & Walsh, Z. (2022). Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 11091. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14512-3

Shao, L.-X., Liao, C., Gregg, I., Davoudian, P. A., Savalia, N. K., Delagarza, K., & Kwan, A. C. (2021). Psilocybin Induces Rapid and Persistent Growth of Dendritic Spines in Frontal Cortex In vivo. Neuron, 109(16). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.06.008

Stamets, P. (2023). Psilocybin Mushrooms and their Tryptamines: Potential Medicines for Neurogeneration [Review of Psilocybin Mushrooms and their Tryptamines: Potential Medicines for Neurogeneration]. In Yale School of Medicine. https://medicine.yale.edu/media-player/stamets-yale-seminar/

World Health Organization. (2023). Depressive Disorder (depression). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression