Psychedelic microdosing has been a focus of media hype and public fascination in recent years. However because of its dubious legal status in most contexts, clinical trials have been limited and microdosing continues to be largely relegated to the realm of anecdotal discussion.

If researchers and practitioners can't even talk openly about real-world use without having to worry about legal or social repercussions, how can we get a systematic view of how people approach it–let alone try to measure its impacts and mechanisms?

Pioneering Examinations

There are, however, some pioneering researchers out there who have been working to advance our understanding and bring the practice of microdosing psychedelics out of the world of word-of-mouth and rumor by harnessing the power of the open science framework to transform anecdotal reports into usable data.

This article leans on two foundational studies that offer an excellent overview of the summary statistics of who microdoses, how, and why. These naturalistic surveys aren't true experiments in the “scientific method” sense, but they aggregate the first hand experiences of thousands of people with experience microdosing psychedelics.

As one of the early pioneers of psychedelic research during the 1960s before criminalization ended most formal experiments, Dr. James Fadiman—known by many as the “father of modern microdosing” returned to his investigatory roots in the very early days of the current so-called psychedelic renaissance. Teaming with Dr. Sophia Korb, this intergenerational team built systematic documentation of microdosing which they published in the Journal of Psychoactive Drugs in their 2019 article, “Might Microdosing Psychedelics Be Safe and Beneficial? An Initial Exploration.” Their rigorous compilation of over 100 in-depth qualitative journals and 1000+ survey responses established critical baseline data on best practices for microdosing including optimal doses and frequencies as well as a transparent record of outcomes–positive, negative and neutral.

Just after Fadiman and Korb's publication, an interdisciplinary research team from Maastricht University in the Netherlands published their own study in the International Journal of Psychopharmacology under the title “Motives and Side-Effects of Microdosing With Psychedelics Among Users.” The team, led by Dr Nadia Hutten, sought generalizable benchmarking around microdosing by launching their own in-depth online survey with over 1100 participants.

Taken together these studies give a rich picture of the practice of psychedelic microdosing.

The contributions of 2000+ combined survey responses, supplemented with the 100+ descriptive testimonies from Fadiman and Korb's participant journals provide both a generalizable statistical view, as well as the nuance of an ethnographic style review.

What Is Microdosing?

Microdosing is the practice of regularly ingesting low doses of psychedelic drugs to stimulate physical, cognitive or emotional benefits through repetitive exposure at what is described as either a sub-perceptual or sub-hallucinogenic threshold.

Many people report acute mood related changes, but lasting changes can take time. Most practitioners agree that microdosing paired with a mindful focus on the user's goals and other positive lifestyle decisions yields the best overall results. It's a practice that is often individual to the person approaching it–and one that often needs to be tailored to that person's needs through some trial and error. In sum, there is no one right way to microdose.

What Kind of People Microdose?

The data says that the microdosing community still skews young, male, and educated, but it is becoming surprisingly diverse. As you might have guessed, microdosing was initially a niche activity for psychonauts and bio-hackers but has continuously expanded appeal.

For example, one of the most popular books on the subject, A Really Good Day, tells the story of a highly accomplished lawyer and author who also happens to be a wife and mother and her experience with microdosing. Google searches for “microdosing” increased by 9x from January 2016 to July 2023.

The Maastricht study gives us some interesting details-although it should be remembered that this is only a reflection of the people that responded to their survey online, so it may contain some bias based on who spends the most time in online forums and similar venues.

According to the team, the microdosing community skews male at 84% of survey respondents, and over 70% had at least some tertiary education (i.e. university, trade school or similar). Additionally, well over half of respondents were based in North America, followed by Europe at about 30%. The most common occupation was "student" at nearly 32%, followed by computer/office workers at 26%. Other significant types of employment included physical work, creative work, and “working with people.” The overall impression is that microdosers tend to be more educated than average, and come from a wide variety of occupations.

source: Hutten et al. (2019)

How Do You Microdose?

There are as many ways to microdose as there are microdosers, but the primary distinguishing factors come down to: What do you use? How much? And How frequently?

What do you use?

Psilocybin (magic mushrooms and truffles) and LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) are essentially tied as the most popular substances for microdosing. The Maastricht study says 59.7% of practitioners have used LSD to microdose at some point and 57.8% have used psilocybin, with some degree of overlap where users have tried both. Beyond LSD and psilocybin, experimenters have reported using a wide range of substances, sometimes stretching the traditional definition of “psychedelics,” including MDMA, mescaline, banisteriopsis caapi (part of the formula of ayahuasca) and a variety of other tools. The vast majority of users ingest their microdoses orally or sublingually as you might expect. A handful inhale it–particularly those that use DMT, and exactly one person claimed to have taken every single substance option on the Maastricht survey rectally…this author is going to go ahead and assume that's either a false response to the survey or all attributable to one particularly intrepid psychonaut.

source: Hutten et al. (2019)

How much?

Not surprisingly, microdosing is meant to employ a very low dose, most commonly, a microdose is about 1/10th of a normal, “recreational” dose. This can differ based on personal preference, considerations like what the user has planned for the day, or just circumstances like how potent the strain or batch the user is working with happens to be or the precision of their dose measurement.

The general standard is that you want to be somewhere along a spectrum from sub-perceptual to sub-hallucinogenic. Put another way: if you microdose and then go for a walk, you might especially enjoy looking at a tree, but the tree shouldn't look back at you. Ultimately, how much a person uses for each microdose is a decision made by each practitioner individually on any given day. The important thing (which the data suggest a lot of people miss) is that you should know how much you're taking.

How often?

How often a person microdoses is something that most people personalize for themselves over time as they discover what works best for them. Their set schedule and content of dosing (and breaks) is known as their protocol. As a starting point, many people use either the Fadiman Protocol, named for James Fadiman, the author of one of the studies discussed here, or the Stamets Protocol, named for another early leader in microdosing. These both offer an easy to follow schedule of on and off days that act as a great jumping off point.

In the Hutten et al. study, almost half of respondents stated that they had designed their own protocol. About a third found their protocol on the internet, and the remainder adopted a schedule based on advice from a friend, a book, or some other source.

Most protocols, including the two mentioned here, recommend “on” days and “off” days in which you do not take an active dose of the psychedelic substance at all in order to give yourself time to process and prevent building a tolerance. Some people microdose just for limited periods while they pursue a specific goal, while others microdose for years at a time. With that said, most people that microdose ongoing normally take periodic breaks to allow their systems to reset to their new baseline.

Why Do People Microdose?

According to Hutten et al., most microdosers do so in the pursuit of performance enhancement (36.6%), especially:

- creativity

- problem solving abilities

- cognitive function

- concentration

- energy

The second most popular reason was to generally improve mood (29.1%), including:

- relief of stress symptoms

- reduced anxiety

- positive mood

14.0% of respondents were microdosing therapeutically for relief from specific symptoms–most often psychological in nature, but sometimes physical too. Among many others, these physical and mental health concerns include:

- treatment resistant depression

- eating disorders

- bipolar disorder

- substance use disorders, such as alcohol dependence and tobacco addiction

Beyond performance enhancement and mental health and wellness, a further 15.2% of respondents were doing it just out of curiosity.

source: Hutten et al. (2019)

Over half of the surveyed respondents said that, far from seeing microdosing as an impairment at work, they actually took their microdoses for work–often in technical and knowledge fields. This is a far cry from the stereotypical view of tie-dyed psychedelics users.

Does microdosing work?

The media narrative surrounding microdosing often falls into one of two camps: it's a panacea that will cure anything from anxiety to back pain to chronic under-achievement OR its effects are all just placebo effect (i.e. imaginary). The studies reviewed here, although not definitive, suggest that something beneficial is happening here.

Both studies indicated at least some positive results in about 80% of respondents. It must be acknowledged again that these are self-reported results to online surveys, so there may be some bias in the data due to successful participants being more enthusiastic, but this remains an impressive result. Some microdosers reported immediate benefits on starting, but by 2 weeks into their regimen, anyone who would see benefits usually had.

The Fadiman/Korb study broke down reported positive results into:

- Change in mood

- Change at work

- Change in home life

Improvement in mood was the most commonly reported outcome. This applied to respondents with clinical diagnoses of psychiatric disorders like major depressive disorder, as well as people without formal diagnoses that were simply pursuing improvement to their current state. An interesting theme among individuals reporting elevated mood effects was that many of those who were currently or previously using anti-depressants believed the benefits of microdosing to be equivalent or superior to pharmaceutical treatments–with the additional benefit of fewer side effects. Many had actually weaned themselves off of pharmaceuticals.

For years, leading edge bio-hackers in tech and similar knowledge work fields have used microdosing as a hack to get an edge professionally. The self-reported results in these surveys make it clear why. Microdosing practitioners that reported changes at work cited improved ability to focus–sometimes despite diagnosed ADHD. Other common benefits included decreased tendency to procrastinate, enhanced creativity and “general productivity” gains.

Reported outcomes in home life were mainly interpersonal in nature. Participants reported that by microdosing a psychedelic substance they were more emotionally open, patient and generous with friends and family members. Psychedelics often encourage the user to adopt new perspectives and set aside entrenched attitudes and behaviors. It is likely this tendency that promotes the more empathic, less guarded stance described.

In addition to these common benefits, there were numerous examples of successful use of microdosing as treatment for ailments such as chronic pain, migraines, addiction, and even the symptoms of PMS. There are deeper explorations of these cases in the broader literature, but they either did not suit the format or weren't common enough to be highlighted in detail in these studies.

What could the downsides of Microdosing be?

Modern microdosing is still a less explored topic, and the physical and emotional frameworks on which it operates are incredibly complex. As such, there are a lot of unknowns. The good news is that most reported negative effects were temporary and relatively minor.

Hutten et al. reported that about 1 in 5 respondents that had microdosed at some point reported some form of negative reaction. Generally, these adverse reactions were acute, so they only lasted as long as microdose was active in the user's system, and were more often psychological than physical.

According to the Maastricht group, about 10% of people experienced psychological downsides when microdosing. They didn't report in detail on the nature of those psychological effects, but according to Fadiman and Korb's work and within the microdosing community, it is understood that this most frequently means something like increased anxiety or depression. It's likely that this is often the result of imprecise dosing resulting in accidental, subtle (or not so subtle) “tripping.”

Hutten et al. also reported that roughly 6% of experimenters experienced physical issues from microdosing. Again, there were not many details in the report, but these issues were mostly reported as minor and short term in nature. Most likely these were insomnia, jittery feelings, fatigue, and stomach upset.

A final group of unlucky individuals experienced both physical and psychological discomfort, and, of the three, they were the ones that most often decided to discontinue the practice. However, it should be noted that, among people who reported to Hutten et al. that they had quit microdosing, it was still more likely due to loss of interest, dissatisfaction with results or successful completion of the user's goals than due to a negative experience.

As with most substances, the personal circumstances of the individual should be taken into account when assessing risk. People with a history of schizophrenia, bipolar or other serious medical or psychological risk factors should consider the hazards carefully and seek advice from an expert.

The other thing to consider and take caution with is the law. Although there are exceptions, many of the substances used for microdosing are illegal in many places around the world. Depending on where you are, the penalties for buying, possessing, or using these substances can be very severe and have serious consequences. Always check your local laws, proceed with caution, and be safe.

How can I improve my chances of successful microdosing?

Psychedelic microdosing still needs more systematic study to explore how best to reinforce its positive effects on well being and cognitive performance. Some people microdose with no other changes to their lifestyle and are happy with their results, but a lot of the most successful practitioners of microdosing do so within a context (physical, mental, and nutritional) designed to give themselves the best results possible. Like some much around microdosing, the actual tactics used varies widely.

Many people set specific intentions or goals for themselves that they invoke when they imbibe. This is often augmented by a practice of mindfulness or meditation. A very simple version of this is to just set aside a little time to be in nature.

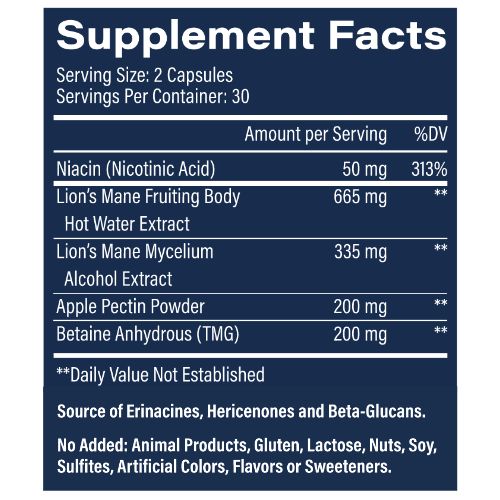

It is a very popular practice to take your microdose as part of a “stack” of complementary nutrients and supplements to promote neuroplasticity and other benefits–some of the most common being lion's mane mushrooms, niacin and a number of nootropics. The most famous combination is the Stamets Stack, named for Paul Stamets (of Stamets Protocol fame). Anecdotal reports and even some nascent scientific literature suggest that using lion's mane mushrooms and niacin in conjuction with psilocybin mushrooms can promote significant improvements in potential benefits vs microdosing the psychoactive drugs alone.

Future Research Opportunities

With the slow but ongoing loosening of regulatory restrictions in many parts of the world, opportunity is rapidly unfolding for future studies of microdosing psychedelics from mental health, well being and cognitive science perspectives.

In a more permissive legislative environment and with proper research funding, researchers could conduct a systematic review to confirm if microdosing practitioners' reported benefits are a result true, statistically confirmed action or just placebo effect.

Early research into mental health concerns such as treatment resistant depression and post traumatic stress disorder suggests these psychedelic interventions, including psilocybin assisted psychotherapy and microdosing, can make significant differences in the lives of patients struggling with mental illness. Future study could provide valuable confirmation.

Beyond treatment of mental health disorders, there is also ample room for future research into the benefits of microdosing psychedelic substances for the enhancement and well being of otherwise healthy volunteers as well.

Finally, the wide range of methods, chosen microdosing substances and and supplementary material and practices employed in microdosing psychedelics leaves scope for multiple comparisons to better understand how best to achieve a significant increase in positive outcomes and avoid any potential drug harms.

In Conclusion

Microdosing has been the target of hype and hate in the media in recent years. It has often been characterized as a trend for hippies and tech bros. Depending on the source, it has been painted as a magical silver bullet for just about any malady you can imagine or a potentially dangerous folly for the gullible.

The truth is a lot more nuanced.

The studies discussed in this article portray a relatively diverse set of participants from various walks of life. They approach it in different ways–sometimes quite controlled, sometimes much looser. Results are equally broad, but demonstrate an encouraging trend of positive outcomes–most frequently in the form of enhanced mental performance, improved mood and healthier interpersonal relations. There are hints at other benefits, such as symptomatic relief from various physical, mental and psychological problems that call out for closer examination.

The legal status of a lot of these substances is shifting in more places all the time, but it will continue to impact progress and the possibility of more broad-based adoption and must be taken into account by anyone considering embarking on a microdosing practice of their own.

There is still a lot to learn, and microdosing is not without risks, but the evidence we have so far demonstrates potential that justifies further investigation by credentialed researchers and citizen scientists alike.

In the end, whether or not to pursue a program of psychedelic microdosing comes down to a personal decision on the part of the individual balancing risk tolerance, what alternatives are available, and the upside potential.

Sources:

Fadiman, J., & Korb, S. (2019). Might Microdosing Psychedelics Be Safe and Beneficial? An Initial Exploration. Journal of psychoactive drugs, 51(2), 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2019.1593561

Hutten, N. R. P. W., Mason, N. L., Dolder, P. C., & Kuypers, K. P. C. (2019). Motives and Side-Effects of Microdosing With Psychedelics Among Users. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 22(7), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijnp/pyz029